Today’s sermon takes the form of a story. This is not my story, although I will tell it in the first person. It is the story of Zechariah, the father of John the Baptist, the man whose story opens the Gospel according to Luke. We have heard the gospel narrative, and now I invite you to imagine with me what Zechariah might say if he could tell us his own story of how God changed his life.

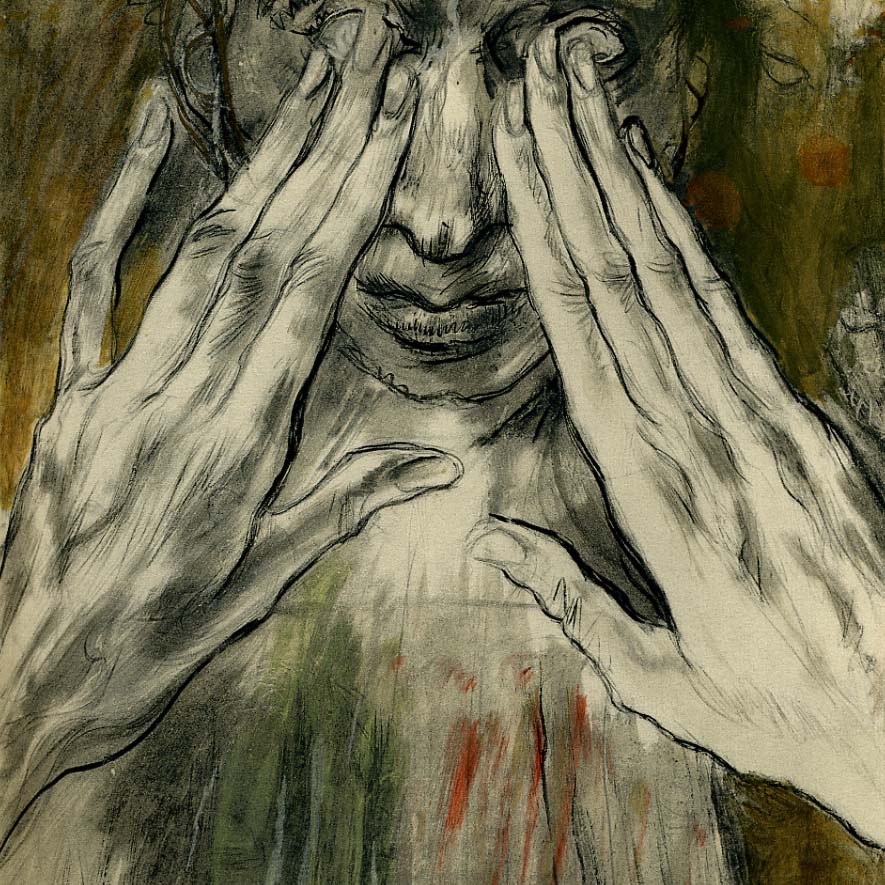

The silence changed everything. Everything. At first I tried to talk, I tried to hum, I tried to rasp, scream, whisper, grunt, whistle, anything I could think of. I lay in bed at night trying everything, my tongue working against my speechless lips, worrying at my teeth, begging in vain for my disobedient vocal chords to comply. Nothing worked – I was completely mute, every attempt to vocalize utterly noiseless. I might as well have been trying to fly.

The silence changed everything. Everything. At first I tried to talk, I tried to hum, I tried to rasp, scream, whisper, grunt, whistle, anything I could think of. I lay in bed at night trying everything, my tongue working against my speechless lips, worrying at my teeth, begging in vain for my disobedient vocal chords to comply. Nothing worked – I was completely mute, every attempt to vocalize utterly noiseless. I might as well have been trying to fly. It was so frustrating to be silent. I’d always been a big talker anyway. I loved to shoot the breeze on a quiet afternoon, to tell stories around the table, to debate about scripture in the synagogue. To be mute now, after this, was unbearable. I had so much to say!

It had been a lifetime of waiting for my wife Elizabeth and me. We’d waited for a child, waiting and waiting and waiting until slowly we accepted that it was too late. We’d waited faithfully for the Messiah, suffering year after year under the Roman imperial occupation, enduring the taxation, the centurions and governors and their tyrannical puppet kings, praying for the day when God would save us and free us. And we’d waited for years for my turn to offer incense in the sanctuary. Each group of priests served for a week twice a year, and each day of that week, one of us would be chosen by lots for the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to approach the Holy of Holies. I had waited, time after time, for my lot to be drawn. The priests God chose for the task seemed to get younger and younger. Sometimes I wondered if God had forgotten us. But not anymore. The silence changed everything.

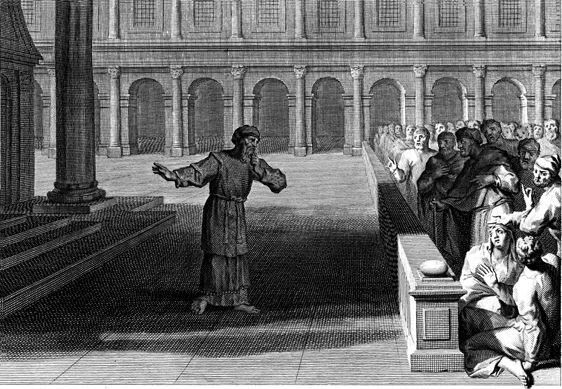

It had seemed like a normal morning as I set off to the Jerusalem temple, joining along the way with the other priests from the order of Abijah. I had pretty much resigned myself by that time, but that day my name was chosen to enter the inner sanctuary and offer the incense. I had entered the chamber prepared to experience the silent, perfect peace of the presence of the Lord. As I lit the incense, there was a rush of wind and a breath-taking, awe-inducing something stood before me, all wings and eyes and sound. I was terrified; my memory is fuzzy, all flashes and snippets. Elizabeth. A son. Name him John. Something about Elijah. Prepare the way of the Lord.

I knew the story of Sarah and Abraham, but still, like a fool, I objected. We were far too old for a child. “I am Gabriel,” came the reply, “an angel sent by God to tell you good news. But since you didn’t believe these words, you will be silent until these things occur.” And it was gone. The inner sanctuary was silent – and so was I.

I can only imagine the look on my face as I stumbled out to the puzzled crowd of priests and found my tongue stopped. I stayed in Jerusalem in a silent daze, until the finally the week ended and I made my way home to Elizabeth in the maddening silence.

So much happened in the silence! Everything with Elizabeth – Liz – changed completely. We’d always gotten along, but it had been different. Liz would laugh at my jokes, listen attentively to my stories, ask insightful questions. I loved that she was a good listener. I was a good talker. But now, I was infuriatingly mute, with the biggest story of my life. I would have written the story down, but Liz couldn’t read it. She’d never learned how; most girls didn’t. I tried to gesture it to her, but what hand signs could possibly communicate this unimaginable being with all the wings and eyes and glory? How can you pantomime “prepare the way of the Lord”? And so we sat in silence, and although the details remained fuzzy, I knew exactly what was happening before Liz realized it, as she started to get queasy, and tired, and more sensitive to smells.

I couldn’t quite remember what the angel had said, but when I would get up at night with a restless Liz, I’d rub her back and remember the stories I’d known all my life. Stories of Abraham and Sarah, Jacob and Rachel, Elkanah and Hannah. A barren woman pregnant, I knew, meant God had special plans for my son. Perhaps, I thought, he was the one we had been waiting for. The one who would break the grip of the Roman empire, who would restore Israel to glory, who would be our savior. Where else but the temple could God possibly foretell the birth of the anointed one? To whom but an elderly barren couple, descendants of great houses, could the Messiah be born? Could anyone imagine a more fitting way for God’s salvation to come to the world? My heart blossomed with pride and vindication, after years of the frustration and embarrassment.

As Liz’s body began to change and she started to realize what was happening, I held her as she wept tears of joy, and laughed in joyful disbelief like Sarah had, so many generations before. I held her as her stories began to bubble forth. I had been embarrassed at her barrenness, pitied by my friends, graciously tolerant of her shortcoming – we had no notion then of the causes, we just all thought that barrenness was God’s curse on certain women, a sign of divine disfavor. I had had no idea what Liz had endured. The years of waiting, the covert glances at her belly, the hushed conversations that stopped when she grew near. The constant references to Sarah and Hannah and their miraculous children. The endless advice, the herbal remedies, the sense of resignation as the weeks and months and years slipped away. The shame she had felt, and the guilt, and the longing. I had never known. Not really. The silence changed everything.

As Elizabeth’s belly grew, so did my certainty that the child to be born was the One we had been waiting for. I know it sounds foolish now, but put yourself in my position. How many of us have thought we knew when and where and how God’s will would be done? How many of us have imagined that the ways of the Lord were predictable and comprehensible? How many of us have looked for God to appear in the time and place we have designated: here, when we are ready, when we are paying attention, where we have prepared space and time for God. In the church, in the Bible study, in the quiet of our hearts in prayer. I am surely not the first, nor the last, who has looked for God where I expected to find God, in places of honor and glory, but has forgotten to look for God among the lowest and the least. I had forgotten, for a while, but the silence changed everything.

Six months after that strange day in the temple, Elizabeth waddled home, ushering along her tiny cousin Mary with a small round belly of her own. I couldn’t believe my eyes. She wasn’t married yet, and if Joseph had any sense he wouldn’t marry her now that she was disgraced. I worried that she’d come here to hide from her shame, that she’d want to stay with us permanently. I didn’t want our child, destined for greatness, mixed up with her child by God only knows who. Although I couldn’t give voice to my dismay, I’m sure my face told the whole story.

In a moment alone, Elizabeth told me, her hushed voice thrumming with joy, how as Mary came up the road, Elizabeth and the child in her womb had recognized the Lord together. Our son had kicked and kicked as if dancing for joy, as both women, normally so reserved, had burst into song. Joseph, through divine intervention or foolish compassion, had not called off the wedding, so Mary would stay until our baby was born, and then make her way home.

And so for three months I sat with the silence, as we all marveled at the things that were taking place among us. For three months I listened to the two of them talk, sharing stories and hopes and fears, trading notes on kicks and aches and pains. I listened to them talk, and I pondered it all in my heart. I pondered how God was working, silent and unseen, in the darkness of these two wombs, in the lives of these two women, in the heart of one silent man learning to really listen. I pondered the breath-taking divide between the God I had been looking for and the Living God who had showed up in my life, moving in such unexpected ways. I wondered to myself, sometimes, what I had missed by thinking I knew what God would not do, where God would not be. I wondered what I might have seen in my life if I had really taken to heart that nothing is impossible with God. I wondered what I might have heard if I had ever stopped talking and really listened as if God might still be speaking, anywhere and everywhere, in the words of my wife, the silence of the early morning, the still small voice which whispers in our hearts.

Elizabeth’s time came, and she gave birth to a son, a beautiful son, a son who would prepare the way of the Lord. Eight days after the child was born, Elizabeth chose a name, the right name, the name told to me: John. I knew that there was no way she could have known the name I had heard that day in the temple, and I knew that Elizabeth had heard God in the silence as surely as I had heard God in the rushing wind and strange voice. I heard the joy in Elizabeth’s voice as she spoke our son’s name, and I heard the scorn of our relatives as they dismissed the name and turned to me. They thought I would contradict Elizabeth. But the silence had changed everything. “His name is John,” I wrote. The sensation of warm, pure light radiated from my fallow larynx, tingled up and down my spine, raised goosebumps on my flesh and poured out my eyes as tears. The silence broke into a thousand glittering pieces as a song of praise poured forth from my lips.

Blessed be the Lord God of Israel

For God has looked favorably upon God’s people, and has redeemed them.

Thanks be to God. Amen.