A Sermon on Luke 18:9-14 for Reformation Sunday

One day about ten years ago, I sat down in the freshman dining hall at my college. It was early in the year, and friendships hadn’t really formed yet, so I had arrived alone, and sat down to eat lunch with two people I recognized. We all had met briefly in the whirl of orientation events, but we didn’t know each other particularly well.

“What does your necklace say?” the young man asked, gesturing at the young woman’s silver necklace.

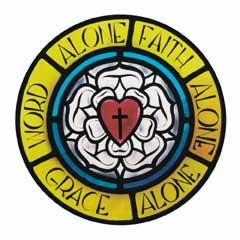

"Sola scriptura, sola gratia, sola fide,” the young woman replied.

“What does that mean?” he asked.

“Scripture alone, grace alone, faith alone,” she answered.

“So it’s a religious thing?” he continued.

“Yes, she answered, it’s a Christian thing.”

“I’m Christian, and I’ve never heard of it,” he mused. So she began to explain.

She was a devout Lutheran, as it so happened, and the words on her necklace were three of the most important theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation. “Sola scriptura” means “scripture alone.” This was a core principle propounded by the Reformers, people like Martin Luther and John Calvin, who were the spiritual ancestors of Lutheran churches like hers, UCC churches like ours, and many other denominations as well. Against a church that claimed the authority to speak on behalf of God, the Reformers declared that all Christian teaching must be based on the Bible – putting the authority to study and discern the will of God back into the hands of any person, clergy or lay, who had access to a Bible and the ability to read it. “Sola gratia” means “grace alone”; the Reformers taught that God’s love is not meted out based on our merits; we do not, and cannot, earn God’s love. God’s love simply comes to us, regardless of anything we do or fail to do. “Sola fide” means “faith alone”; Reformers like Martin Luther and John Calvin saw that many Christians – lay and clergy – treated the life of faith as if it were a to-do list: check off all of the boxes, and you would be saved. Against this, they asserted that faith in God is all that is required for salvation, and is the only path to salvation – not going to church, not refraining from sin, not praying every morning and night, not giving all your money to charity – simply faith.

The young woman at the dining hall table explained the three tenets to us (although perhaps not in those exact words) - beliefs that I would later encounter again and again in my studies as a religion major and then a seminary student. And she concluded with something like, “So that’s why Catholics are wrong.”

“Are there a lot of Catholics where you’re from?” the young man asked.

“No, I’ve never actually met one before,” she answered.

“I’m Catholic,” he told us.

“…Oh…” she said, with obvious discomfort.

We all hurried through our lunches, talking about the weather and our class schedules, and I haven’t seen much of them since. But the story comes to mind on this day, Reformation Sunday, as we remember the Protestant Reformers who are the spiritual ancestors of our faith community. And it comes to mind especially as we encounter today’s Gospel lesson, a parable from the Gospel according to Luke.

Speaking to an unfriendly audience, Jesus tells them this parable: two men went to the temple to pray. One was a Pharisee. Now, the Pharisees and the early Christians were often at odds with each other, and so the Christian tradition has come to hear the word “Pharisee” as if it simply meant “bad guy” or “hypocrite.” But the Pharisees were more than that. In a culture where religious observance was largely the purview of religious elites, the Pharisees advocated for more robust religious practice in the daily lives of everyday people. They wanted religion to be practiced by the people, not just seen to by the priests – a concern that they shared with the Protestant Reformers hundreds of years later.

So a Pharisee went to the temple to pray, and he said, “God, I thank you that I am not like other people: thieves, rogues, adulterers, or even like this tax collector. I fast twice a week; I give a tenth of all my income.” Well, that’s pretty repulsive, right? Giving thanks for his superiority to others is a rather arrogant prayer. And yet, he does have reason to boast: he fasts twice a week and gives a tenth of his income, he says. That is to say, he is really making some serious sacrifices to put his faith at the center of his life. One commentator I read observed that churches would be glad to have more members like this Pharisee – who pour their energy into their religious community and life of faith.

Meanwhile, the tax collector also prays. Tax collectors are another set of stock characters in scripture who are unfamiliar in our modern context (they’re not at all like IRS agents), but unlike Pharisees, who get cast as bad guys because they were in a theological debate with the early Christians, tax collectors were universally despised in Jesus’ context. They paid the Roman authorities a fixed amount for the privilege of extracting exorbitant taxes from Rome’s colonial subjects by any means necessary. They collected as much money as they could bully and brutalize out of the people of their region, paid a set amount to Rome, and got to keep however much was left. They were collaborators with an oppressive imperial regime, their income was squeezed out of people who often were barely subsisting, and they were hated for it. But this tax collector goes to the temple to pray and, Jesus says, he “would not even look up to heaven” to pray; his posture is humble. He beats his breast and prays, “Lord, be merciful to me, a sinner.” Jesus declares that the tax collector “went home justified,” unlike the Pharisee. “All who exalt themselves will be humbled, but all who humble themselves will be exalted,” Jesus concludes.

It is an apt parable to hear on Reformation Sunday, and the temptation would be to cast the Reformers and those who follow them as the tax collector, and the Catholic church they stood against as the Pharisee. Unlike the Pharisee, who believes he can earn his way into God’s heart through fasting, prayer, and tithing, the theology of the Protestant Reformation places the emphasis on God’s love and forgiveness. The emphasis is on God’s faithfulness, not on human faithfulness. Reformed theology emphasizes that we are imperfect – that we mess up and fall short. It teaches that our relationship with God is not predicated on our being good enough. God will always be reaching out to us, because God is loving and gracious and merciful. This parable is kind of a prime example of “sola fide” and “sola gratia.” It would be tempting to conclude that, like the tax collector who puts his faith in God’s grace, we must remember our spiritual heritage and cling tightly to the legacy of the reformers.

The problem is that, if we followed that interpretation through to its logical conclusion, we might then conclude with a sentiment like this: “God, we thank you that we are not like the Pharisee. We understand theology. We believe in grace and mercy.” And then we would be right back where we started: like the Pharisee, we would be patting ourselves on the backs for having it right, and looking down our noses at those whom we think have gotten it wrong – defining our faith not as a positive expression of our relationship with God through Christ, but in contrast to inaccurate stereotypes of other faith traditions.

Like that young woman in the freshman dining hall, like the Pharisee in the parable, it is tempting to define ourselves based on our assumptions of our own superiority. God, we thank you that we are not like the tax collector. God, we thank you that we are not like the Pharisee.

God, we thank you that we are not like the Catholics, or the fundamentalists, or those fancy Manhattan churches where you’d better have just the right clothes and plenty of money. God, we thank you that we are not like the churches that oppose LGBT inclusion. God, we thank you that we are not like all those people who show up at church only on Christmas and Easter. God, we thank you that we are not like those people who think watching a televangelist counts as going to church. God, we thank you that we are not like that young woman in the freshman dining hall.

Jesus tells us this parable of the Pharisee and the tax collector not so that we can judge the judgmental Pharisee, but to invite us to reconsider how self-righteousness and judgment might stand in the way of our own relationship with God. The Pharisee’s prayer reveals that he is so concerned about how he measures up in God’s eyes that his view of God’s creation is distorted. “I thank you that I am not like other people,” he says. But the other people he names are all children of God, created in God’s image, people who make mistakes and fall short, people who judge others and doubt themselves, people who are capable of love and courage and faithfulness. People from whom the Pharisee might learn something about God, if he had ears to hear. And as we hear this parable, the judgment we feel toward the Pharisee reminds us that we, like him, sometimes slip into judgment and condemnation. Like him, we sometimes forget that in God’s eyes, we are all equally beloved and beautiful, not because of what we have done or failed to do, but simply because we are children of God. And God loves us not because we are better or more correct than other people, but simply because God loves us.

So as we hear this parable on this Reformation Sunday, let us give thanks for our spiritual heritage not because it makes us better than other traditions (I'm not sure it does), but because it draws us closer to the God who made us all, Pharisees and tax collectors and everything in between. The God who loves us all, Protestants and Catholics and everyone else. The God who has mercy on us all, saints and sinners and those of us – all of us – who are a little of both.

Amen.

Thursday, October 31, 2013

Not Like Other People

Labels:

bible,

catholicism,

grace,

imago dei,

jesus,

new testament,

parables,

reformation,

sermon

Sunday, October 6, 2013

The Prodigal Manager

A sermon on Luke 16:1-13

Note: The sermon will make more sense if you read the parable first.

It’s a little bit embarrassing that I have opened so many sermons in the last couple of months by telling you how difficult it is to preach on whatever passage has been assigned for that Sunday. I had really hoped not to do it this week. So I opened my Bible with hope and determination, and found myself utterly puzzled by the Gospel passage. Not to be deterred, I opened my commentaries and navigated to my favorite lectionary blogs to find a little interpretive assistance. Commentator after commentator declared unequivocally that this week is known as Jesus’ most inexplicable parable.

Perhaps the problem is not with the parable, but with how we are trying to interpret it. Christian interpreters have a tendency to approach the puzzling and confusing passages of the Bible as if they were algebra problems. If we just do enough research, we imagine, the correct answer will emerge. Find the right theological concept, or Old Testament reference, or alternate meaning of a Greek word, and solve for X. The Jewish tradition, of which Jesus and the disciples were part, has other modes of interpretation that might fit better for us today. The practice of “midrash” takes those puzzling places and intriguing gaps in scripture as jumping-off points, imaginatively fleshing out characters and events with a rich tradition of stories. From this point of view, a confusing scripture is not a problem to be solved, but an opportunity for faithful imagination. Rather than an algebra equation with one correct answer, we could envision it as a melody line in need of harmonization. It’s not that “anything goes”: there are plenty of notes that will create jangling discord rather than transcendent harmony; but with study, prayer, and inspiration, there are countless ways to add to the music.

In that spirit, I am going to tell you three very short stories today, stories in the voices of three of the characters in this parable, as we imagine together what Jesus might have been saying in this parable about the rich man, the manager, and the debtors.

I

This is the first story, the story of the debtor:

A hundred jugs of oil is a lot of oil. I didn’t know if I would ever be able to pay it back. Olive oil isn’t cheap now, for all your industrialization and mechanization, but imagine what it cost us then, how much labor went into cultivating those olive groves and pressing out the oil in presses of rough-hewn stone and wood. A hundred jugs of oil I owed! Even the fifty I originally borrowed was a lot – too much – but what choice did I have? My kids needed to eat. You all talk about credit card debt and student loan debt and home owners’ debt as if debt were a twenty-first century problem, but believe me, debt is an old, old thing.

I knew that I had borrowed fifty, and Josiah the manager knew I was borrowing fifty, and the rich man Nicodemus would have known I was borrowing fifty if he kept his own books. But the Torah laws forbid charging interest. And in a world like ours, that was never going to work – no one was going to lend out of the kindness of their hearts – so everyone just knew the workaround. You would just write down the larger amount, as though that was what you had borrowed to begin with. Oil you have to pay back double, because it’s risky. The jugs can crack, or the oil can go rancid, and then the lender is out of luck.

Anyway, word got around one day that Josiah had been less than scrupulous with the books – something about sneaking food to someone and trying to cover it up. Nicodemus had caught wind of it and was firing him. When I got word that Josiah wanted me to come and see him right away, I was afraid that my loan was about to be called in. I didn’t have the hundred jugs of oil. I might, someday, be able to repay the original fifty, but not a hundred. Not today. I rushed to Nicodemus’s property, terrified by visions of what would happen to me and my children when I couldn’t pay up. Debtor’s prison? Slavery?

But that’s not what happened at all. “How much do you owe?” Josiah asked. “A hundred jugs of oil,” I replied. “Are you sure?” Josiah inquired, looking at me significantly, “I could swear I only gave you fifty.” He was right, of course; fifty is what I’d borrowed. “Let’s correct this bill,” Josiah said smoothly. And it was done, the illicit interest forgiven and my debt halved in the stroke of a pen. The reduction of my debt gave me relief, peace of mind, hope, a chance at freedom, finally, from the debt that had weighed on me. Did he do it for selfish reasons? Maybe he did. But blessing came from it anyway: when Josiah came to my door, I had something to offer: a place to stay and a warm meal for someone who had once been a debt collector, but was now a friend in need. It was a blessing and a gift to have something to offer; I, who had always had to ask and borrow and receive, was able to extend hospitality and kindness, grace freely given, as I had freely received. Thanks be to God.

II

This is the second story, the story of the manager:

You start off with the best intentions. Or at least, I had. I was hired to manage Nicodemus’s property and I swore to myself that I wouldn’t be like those other managers. You see, managers didn’t get a fixed salary, paid by the employer. Instead, their income came from extra charges to the borrowers. Someone borrows fifty jugs of oil, say, and pays back a hundred to the property, and a few to the manager as well. Tax collectors make their money the same way, but they’re even less popular, since they work for the Romans.

I never wanted to be one of the bad guys, squeezing wealth out of the desperation of the poor, but what could I do? You have to feed your kids somehow. And you want a decent pair of sandals, and maybe to eat meat at dinner every so often, and some wine. And would it really be so bad to get one piece of jewelry for your wife? Next thing you know, you’re charging as much as those guys you hated – or even more!

I felt so guilty all the time, but I just didn’t know what to do. I lived every day with this gnawing, vague sense of helplessness and shame. Sometimes I’d try to soothe my conscience – someone would come who would never be able to pay back their debt, and I’d lend to them and just never follow up. Someone in terrible need, just on the edge of ruin. I’d try to make it come out right in the books, but it never quite did.

I guess Nicodemus must’ve found out about one of them, because one day he sent me a message: he was going to need an accounting of the property, because he wasn’t going to employ me anymore. I summoned everyone who was indebted to Nicodemus, and I could feel this palpable sense of dread, as they all waited to talk to me. I could see them all, the ones I had given a break to, and the ones I had overcharged to try to cover for it, and I knew they all just hated me.

But here’s the thing: I knew my job and my comfortable life were slipping away; there was nothing I could do anymore to try to hold on to them. And once I knew that, all of the rules that had kept me bound up with guilt and worry melted away, and I knew what to do. There would be grace and mercy poured out into my life in the days to come, but I didn’t know that yet. I just knew that in the few hours I had left managing Nicodemus’s property, I finally could be faithful to the one who made me, instead of the one who employed me; I finally could serve God instead of wealth. In that room, I turned away from everything I was supposed to do, and I canceled debts left and right. I proclaimed good news to the poor, and release to those captive to crushing debt. And the Spirit of the Lord was upon me. Thanks be to God.

III

This is the third story, the story of the rich man:

I know that, comparatively speaking, I never had much to complain about. Feeling conflicted about being rich doesn’t hold a candle to the worries of families who can’t feed all their kids. I know. But there it was: I felt conflicted about my wealth. Guilty, even. I knew that the scriptures didn’t look kindly on the rich. I tried to figure out what to do about it, sometimes, but I just felt stuck. I didn’t go around making “the ephah small and the shekel great,” as the prophet Amos once wrote, but the laws against charging interest? I couldn’t just give out free money. I was rich, not stupid.

There were nice things about being wealthy, but the lending and the collecting and the accounting… it was all so uncomfortable. I was relieved to finally hire Josiah to handle things. He seemed to be doing a fine job, so mostly I just let him handle things; it was easier that way, and the less I thought about it, the less guilty I felt.

Everything was going smoothly until one evening when I was at a dinner party, where I heard from a friend that Josiah had given a winter’s worth of food to a poor widow out of my storehouses. I guess he thought he’d be able to cover it up, but she’d let it slip to the other women at the well. The story was all over town, and I was a laughing stock. I would have been willing to give the widow the food if Josiah would have just asked me, but to find out that he’d been stealing from my stores like that and trying to cover it up? I was furious. I got up the next morning and went to demand a thorough accounting, sending a messenger ahead of me.

By the time I got there, though, Josiah had taken matters into his own hands. He had canceled the interest on every single loan, and I’m pretty sure that some debts had been canceled altogether. Pride, fear, and defiance mingled on Josiah’s face. I know I should’ve been angry, but to be honest, we were so far past that that all I felt was a kind of relief, a sense of freedom. It was like all the wealth I’d accumulated had trapped me under its weight, and I didn’t realize how constricting and suffocating it was until it started to lift.

I think Josiah expected me to fire him, or worse. I probably could’ve had him thrown in jail. But I looked around at the people he had freed from debt and fear and anxiety, and I knew he had freed me as well. And so I thanked him, and I asked him to do one last thing as the manager of my property: to give it all away to whoever needed it. That night, with little more than the shoes on my feet, the clothes on my back, and the walking stick in my hand, I left my old life behind and started down the road. I’d heard there was a rabbi traveling the countryside, feeding the hungry, healing the sick, and teaching about a kingdom where grace and mercy flow like cool water. I set out to follow him. Thanks be to God. Amen.

Note: The sermon will make more sense if you read the parable first.

It’s a little bit embarrassing that I have opened so many sermons in the last couple of months by telling you how difficult it is to preach on whatever passage has been assigned for that Sunday. I had really hoped not to do it this week. So I opened my Bible with hope and determination, and found myself utterly puzzled by the Gospel passage. Not to be deterred, I opened my commentaries and navigated to my favorite lectionary blogs to find a little interpretive assistance. Commentator after commentator declared unequivocally that this week is known as Jesus’ most inexplicable parable.

Perhaps the problem is not with the parable, but with how we are trying to interpret it. Christian interpreters have a tendency to approach the puzzling and confusing passages of the Bible as if they were algebra problems. If we just do enough research, we imagine, the correct answer will emerge. Find the right theological concept, or Old Testament reference, or alternate meaning of a Greek word, and solve for X. The Jewish tradition, of which Jesus and the disciples were part, has other modes of interpretation that might fit better for us today. The practice of “midrash” takes those puzzling places and intriguing gaps in scripture as jumping-off points, imaginatively fleshing out characters and events with a rich tradition of stories. From this point of view, a confusing scripture is not a problem to be solved, but an opportunity for faithful imagination. Rather than an algebra equation with one correct answer, we could envision it as a melody line in need of harmonization. It’s not that “anything goes”: there are plenty of notes that will create jangling discord rather than transcendent harmony; but with study, prayer, and inspiration, there are countless ways to add to the music.

In that spirit, I am going to tell you three very short stories today, stories in the voices of three of the characters in this parable, as we imagine together what Jesus might have been saying in this parable about the rich man, the manager, and the debtors.

I

This is the first story, the story of the debtor:

A hundred jugs of oil is a lot of oil. I didn’t know if I would ever be able to pay it back. Olive oil isn’t cheap now, for all your industrialization and mechanization, but imagine what it cost us then, how much labor went into cultivating those olive groves and pressing out the oil in presses of rough-hewn stone and wood. A hundred jugs of oil I owed! Even the fifty I originally borrowed was a lot – too much – but what choice did I have? My kids needed to eat. You all talk about credit card debt and student loan debt and home owners’ debt as if debt were a twenty-first century problem, but believe me, debt is an old, old thing.

I knew that I had borrowed fifty, and Josiah the manager knew I was borrowing fifty, and the rich man Nicodemus would have known I was borrowing fifty if he kept his own books. But the Torah laws forbid charging interest. And in a world like ours, that was never going to work – no one was going to lend out of the kindness of their hearts – so everyone just knew the workaround. You would just write down the larger amount, as though that was what you had borrowed to begin with. Oil you have to pay back double, because it’s risky. The jugs can crack, or the oil can go rancid, and then the lender is out of luck.

Anyway, word got around one day that Josiah had been less than scrupulous with the books – something about sneaking food to someone and trying to cover it up. Nicodemus had caught wind of it and was firing him. When I got word that Josiah wanted me to come and see him right away, I was afraid that my loan was about to be called in. I didn’t have the hundred jugs of oil. I might, someday, be able to repay the original fifty, but not a hundred. Not today. I rushed to Nicodemus’s property, terrified by visions of what would happen to me and my children when I couldn’t pay up. Debtor’s prison? Slavery?

But that’s not what happened at all. “How much do you owe?” Josiah asked. “A hundred jugs of oil,” I replied. “Are you sure?” Josiah inquired, looking at me significantly, “I could swear I only gave you fifty.” He was right, of course; fifty is what I’d borrowed. “Let’s correct this bill,” Josiah said smoothly. And it was done, the illicit interest forgiven and my debt halved in the stroke of a pen. The reduction of my debt gave me relief, peace of mind, hope, a chance at freedom, finally, from the debt that had weighed on me. Did he do it for selfish reasons? Maybe he did. But blessing came from it anyway: when Josiah came to my door, I had something to offer: a place to stay and a warm meal for someone who had once been a debt collector, but was now a friend in need. It was a blessing and a gift to have something to offer; I, who had always had to ask and borrow and receive, was able to extend hospitality and kindness, grace freely given, as I had freely received. Thanks be to God.

II

This is the second story, the story of the manager:

You start off with the best intentions. Or at least, I had. I was hired to manage Nicodemus’s property and I swore to myself that I wouldn’t be like those other managers. You see, managers didn’t get a fixed salary, paid by the employer. Instead, their income came from extra charges to the borrowers. Someone borrows fifty jugs of oil, say, and pays back a hundred to the property, and a few to the manager as well. Tax collectors make their money the same way, but they’re even less popular, since they work for the Romans.

I never wanted to be one of the bad guys, squeezing wealth out of the desperation of the poor, but what could I do? You have to feed your kids somehow. And you want a decent pair of sandals, and maybe to eat meat at dinner every so often, and some wine. And would it really be so bad to get one piece of jewelry for your wife? Next thing you know, you’re charging as much as those guys you hated – or even more!

I felt so guilty all the time, but I just didn’t know what to do. I lived every day with this gnawing, vague sense of helplessness and shame. Sometimes I’d try to soothe my conscience – someone would come who would never be able to pay back their debt, and I’d lend to them and just never follow up. Someone in terrible need, just on the edge of ruin. I’d try to make it come out right in the books, but it never quite did.

I guess Nicodemus must’ve found out about one of them, because one day he sent me a message: he was going to need an accounting of the property, because he wasn’t going to employ me anymore. I summoned everyone who was indebted to Nicodemus, and I could feel this palpable sense of dread, as they all waited to talk to me. I could see them all, the ones I had given a break to, and the ones I had overcharged to try to cover for it, and I knew they all just hated me.

But here’s the thing: I knew my job and my comfortable life were slipping away; there was nothing I could do anymore to try to hold on to them. And once I knew that, all of the rules that had kept me bound up with guilt and worry melted away, and I knew what to do. There would be grace and mercy poured out into my life in the days to come, but I didn’t know that yet. I just knew that in the few hours I had left managing Nicodemus’s property, I finally could be faithful to the one who made me, instead of the one who employed me; I finally could serve God instead of wealth. In that room, I turned away from everything I was supposed to do, and I canceled debts left and right. I proclaimed good news to the poor, and release to those captive to crushing debt. And the Spirit of the Lord was upon me. Thanks be to God.

III

This is the third story, the story of the rich man:

I know that, comparatively speaking, I never had much to complain about. Feeling conflicted about being rich doesn’t hold a candle to the worries of families who can’t feed all their kids. I know. But there it was: I felt conflicted about my wealth. Guilty, even. I knew that the scriptures didn’t look kindly on the rich. I tried to figure out what to do about it, sometimes, but I just felt stuck. I didn’t go around making “the ephah small and the shekel great,” as the prophet Amos once wrote, but the laws against charging interest? I couldn’t just give out free money. I was rich, not stupid.

There were nice things about being wealthy, but the lending and the collecting and the accounting… it was all so uncomfortable. I was relieved to finally hire Josiah to handle things. He seemed to be doing a fine job, so mostly I just let him handle things; it was easier that way, and the less I thought about it, the less guilty I felt.

Everything was going smoothly until one evening when I was at a dinner party, where I heard from a friend that Josiah had given a winter’s worth of food to a poor widow out of my storehouses. I guess he thought he’d be able to cover it up, but she’d let it slip to the other women at the well. The story was all over town, and I was a laughing stock. I would have been willing to give the widow the food if Josiah would have just asked me, but to find out that he’d been stealing from my stores like that and trying to cover it up? I was furious. I got up the next morning and went to demand a thorough accounting, sending a messenger ahead of me.

By the time I got there, though, Josiah had taken matters into his own hands. He had canceled the interest on every single loan, and I’m pretty sure that some debts had been canceled altogether. Pride, fear, and defiance mingled on Josiah’s face. I know I should’ve been angry, but to be honest, we were so far past that that all I felt was a kind of relief, a sense of freedom. It was like all the wealth I’d accumulated had trapped me under its weight, and I didn’t realize how constricting and suffocating it was until it started to lift.

I think Josiah expected me to fire him, or worse. I probably could’ve had him thrown in jail. But I looked around at the people he had freed from debt and fear and anxiety, and I knew he had freed me as well. And so I thanked him, and I asked him to do one last thing as the manager of my property: to give it all away to whoever needed it. That night, with little more than the shoes on my feet, the clothes on my back, and the walking stick in my hand, I left my old life behind and started down the road. I’d heard there was a rabbi traveling the countryside, feeding the hungry, healing the sick, and teaching about a kingdom where grace and mercy flow like cool water. I set out to follow him. Thanks be to God. Amen.

Labels:

bible,

economic justice,

first person narrative,

forgiveness,

grace,

jesus,

new testament,

parables,

sermon

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)